What analytical draft value curves are missing about NFL roster building

We've come a long way since the days of the Jimmy Johnson draft chart, but newer analytical draft value curves are still missing critical context

Every draft post-mortem includes a battle between various fan bases and the nerds on whether their favorite team’s general manager made the appropriate cost-benefit decision or was fooled by overconfidence. It’s the classic battle of conventional wisdom and institutional authority versus outsiders with advanced tools of modeling and valuation. While the tide has shifted towards the latter in recent times, traditions die hard.

THE CHART THAT CHANGED THE NFL DRAFT

For decades the currency of NFL draft picks was determined by a point system created way back in 1991 by petroleum engineer and Cowboys minority owner Mike McCoy. What’s conventionally known as the “Jimmy Johnson chart” was McCoy’s remarkably accurate point-value assessment of each and every NFL draft slot.

McCoy crafted pick values to reflect the historical pick trades, not the fundamental value of the picks. The Jimmy Johnson chart quantified the conventional wisdom of the market, which was previously a messy, somewhat random assortment of intuition-based trades.

Johnson leveraged the concrete values of his chart into confident wheeling-and-dealing, trading up and down in the first round of the 1991 draft four different times, then making a whopping 12 pick trades in the 1992 NFL draft. Johnson could trade for, flip and re-flip the same picks with rapidity knowing that all he had to do was find one of numerous potential trade partners misvaluing an opaque market, creating instantaneous excess value.

A chart with no explicit link to actual player value shouldn’t continue to hold much sway in the age of sports analytics, but it does in the NFL. As one of the more analytically savvy NFL franchises tells it:

“We still use it as a baseline,” said Buffalo Bills General Manager Brandon Beane, echoing the sentiment of many fellow GMs. “We do use other [charts], but we still reference it as a starting point.”

CONNECTING DRAFT PICKS TO PLAYER VALUE

The efforts of more analytically inclined analysts have broadened our understanding of draft pick value, mostly by attaching it to what teams care about most: player value on the field. In 2005, professors Cade Massey and Richard Thaler wrote the seminal “The Loser’s Curse” study of NFL draft value, introducing the foundational metric for measuring the benefit of draft picks: surplus value.

We define surplus value as the player’s performance value – estimated from the labor market for NFL veterans – less his compensation.

Every NFL draft pick has an assigned rookie contract value, or cost to the NFL that drafts him. Surplus value is the difference between the assigned contract cost and an estimate of what it would cost an NFL team to acquire or retain a similarly productive player in free agency or via contract extension. In a hard cap league, all players have to be valued against the cost of their services, and rookie salary schedules typically undervalue the likely productivity of drafted players, creating value for the teams that draft them.

Through the years other have refined the concept of surplus value to base it on different measurements of player value (PFF WAR), different wage scales (Fitzgerald-Spielberger), and Massey-Thaler themselves updated their original analysis to account for changes to the rookie wage scale incorporated in the CBA agreed to after the 2011 lockout.

All of these assessments pointed in the same direction: the historical trade values quantified in the Jimmy Johnson chart placed too big of a premium on higher picks, leaving excess surplus value for teams willing to move down in the draft.

Why did teams overvalue earlier draft picks? Massey and Thaler point to overconfidence, among other factors.

Another robust finding in psychology … is that people are overconfident in their judgments. Furthermore, overconfidence is exacerbated by information—the more information experts have, the more overconfident they become.

There are few decision-makers in any field who have to deal with a bigger firehouse of information than NFL front offices. Every prospect has numerous metrics for stats, film assessments, interviews, references, medicals, etc. Logic backs up what every analytical study of draft value has shown: NFL decision-makers systematically overvalue the benefits of moving up to get one particular player over another, assuming they have a better evaluation than the rest.

The most counterintuitive conclusion of the analytical studies is that the rapidly increasing compensation for top-5 NFL draft picks makes them less valuable in terms of surplus value than those that come later. As illustrated here by Timo Riske in his analysis using PFF WAR, total value (here using PFF WAR) for players selected in the draft increases all the way to the first selection, but not as rapidly as rookie contract value, placing the peak for surplus value outside of the top-10 picks.

WHAT THE NERDS ARE MISSING (AS DETERMINED BY OTHER NERDS)

While all of these charts solved the fundamental issue of attaching pick value to the value of the players selected, there are more concerns for building an NFL roster than maximizing the average pick value of each selection. The average values for each draft position reflect a range of outcomes. While all NFL teams need a variety of talent levels, there could naturally be a premium for truly high-end, elite talent.

In his days before becoming the director of data and analytics for the NFL, Michael Lopez, in a post entitled “Rethinking draft curves,” looked specifically at the likelihood of finding superstar talent at different draft positions - defined as the 95th percentile in career approximate value - and found that the curve for average value didn’t match that of likelihood of finding a superstar player at the draft position. The probability curve for finding a superstar player rose more steeply at the top of the NFL draft than that for an average player, and Lopez suggested that perhaps a better draft curve might incorporate both in the form of a “blended” valuation.

NFL rosters have size constraints, and teams can only put 11 players onto the field at one time. Even if you hit the average values for Day 3 picks, you might not be able to extract the same value on the field as you could with multiple superstars and more room to fill in around them.

ROSTER BUILDING IS A HOLISTIC EXERCISE

We’ve identified one (previously identified) flaw in the general assessment that all draft picks should be valued on their average expectation. But there is a greater piece of the puzzle missing from treating all picks the same, no matter which position will be drafted.

There has been a carve-out for quarterbacks in most recent assessment of draft pick value, as we’ve come to understand that the most important position on the field can’t be lumped in with others in determining pick value curves. Despite the success of somewhat later drafted quarterbacks like Lamar Jackson and Jalen Hurts (yeah, yeah, Tom Brady), still the the vast majority of the elite NFL quarterbacks were taken near the top of the NFL draft. If you want to find the next Patrick Mahomes (10th pick), Josh Allen (7th), Joe Burrow (1st) or Justin Herbert (6th), you’ll probably need to spend make a top-10 selection. While NFL front offices still might be overconfident in ranking their quarterback assessments, Massey and Thaler found that it was less so than for other positions.1

Ben Baldwin recreated a Massey-Thaler-type surplus value analysis, specifically excluding quarterbacks from the analysis with the understanding they should be treated differently. Baldwin found the familiar relationship between on-field value (measured by veteran contract APY as a percentage of the cap), rookie contract value (APY) and the difference in surplus value. The peak comes at around the 12th selection for non-quarterbacks.

It’s great to take the outsized effect of quarterback value out of the equation, but could we be missing something by treating all non-quarterbacks equally. We argue ad nauseam about the value of running backs, so why lump them in with higher positional value roles in our analysis.

I liberally borrowed (copy & pasted) code from Baldwin to re-create his analysis, but instead of putting all the players in the same bucket, I divided them by position. When you see the different positions side by side, it becomes clear the disparate positional valuations, especially at the top of the draft.

While the average surplus value for all non-quarterbacks peaks at around 3.5% of the cap (12th pick), for offensive tackles it’s over a full percent higher, and nearly equally high for interior defensive line and edge rusher. For a lower position value roles like interior offensive line, linebacker, running back, tight end and safety, you can find peak surplus value in the second round.

When deciding how to allocate first-round selections, and whether it’s worth trading up to make that selection, the position you’re targeting is highly important, even between non-quarterbacks. Draft value charts and curves can’t accurately tell you the value loss in terms of roster building trading out of the first round and needing to find rapidly decaying surplus value positions like edge rusher and interior defensive linemen.

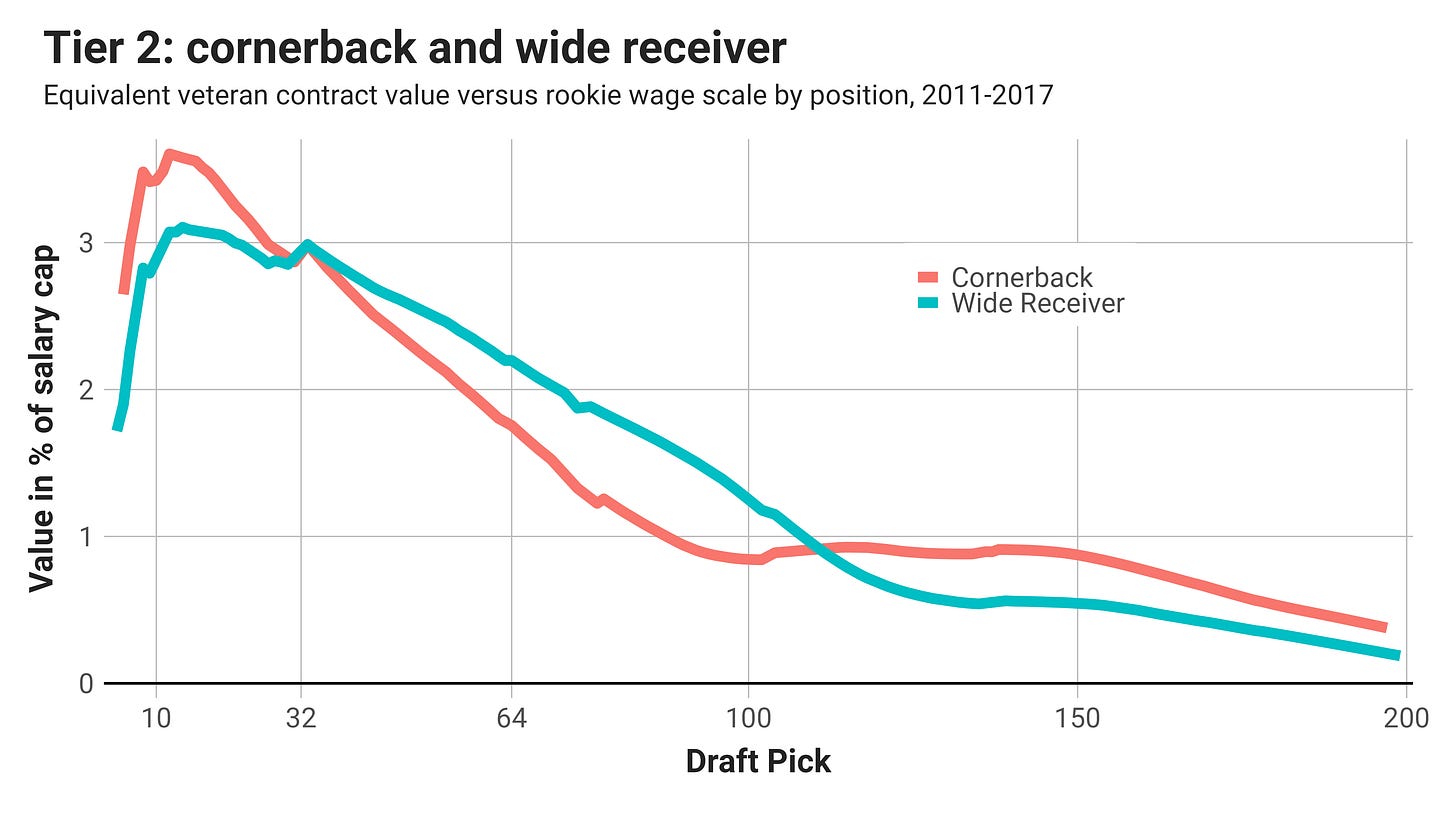

To simplify the visual a bit further, I divided the positions into tier based upon their peak first-round surplus value: greater than 4% (Tier 1, offensive tackle, interior defensive line and edge rusher), between 3-4% (Tier 2, cornerbacks and wide receivers) and less than 3% (Tier 3, interior offensive line, linebacker, running back, tight end and safety.

This separation illustrates the differential of value in the first round of the draft for tier 1 versus those the second round and beyond, when the surplus value doesn’t differ much from tiers 2 & 3. In fact, a similar relationship exists between tier 2 and 3, where the former’s first-round surplus value advantage narrows quickly in later rounds.

A holistic draft strategy needs to factor in not only the surplus value of the pick generally, but the opportunity cost of being unable to fill tier 1 & 2 positions if you use early picks on positions in tier 3. Trading back can get you more picks, but there is a hard limitation on the number of first round picks available teams, and those picks needs to be used on tier 1 (and maybe tier 2) players in order to find the most total value for the entire roster. Too much trading back will allow you to have good chances and filling tier 2 & 3 positions at a lower cost, but you’re much less likely to reap the significant surplus value gains of tier 1 beyond the first round.

Another piece of the holistic roster building strategy is free agency, and this analysis pairs well with my earlier research identifying the tier 3 positions on offense and defense as the best values of offseason signings. Filling those roles before the draft, even if it includes free-agency premiums and overpaying, can be smart. With lower value roles secured, teams can free up earlier picks for more important positions, eliminating the temptation to make a low-upside pick in the first round.

FOCUSING IN ON POSITIONAL VALUE TIERS

I separated the different tiers below so you can get a better read on how each position shifts in surplus value through the first 200 picks in the NFL draft. One note on offensive tackle, if you separate it further by left and right tackle, the lines basically overlap, though no primary right tackle has been selected in the top-3 picks.

It’s hard to say the exact priority ordering between offensive tackle, interior defender and edge rusher. Tackles give you the most surplus value through the first round, but also have a less steep drop through the second round. Beyond round 2, the relationship flips again, with some decent surplus value for the defensive positions and nearly nothing left a tackle after Day 2.

Cornerback and wide receiver could almost be in different tiers. Cornerbacks have a materially higher surplus value peak in the early and middle first round, then wide receivers become better selections in the second and third rounds.

At the bottom of the positional value scale, there’s a wide variety of surplus value in different draft positions. Interior offensive line is higher than the rest in the first round, but has a higher peak in the early second round, and maintains strong surplus value through the middle of the third round.

Linebacker and running back have many similarities, with the curves nearly tracking each other through the end of the second round, then running back value falling off significantly. The holistic approach could be to entire ignore the running back position on the first two days of the NFL draft.

Tight end has the flattest surplus value curve, mostly because so few first-round tight ends have ended up elite players, while Hall-of-Fame caliber players like Rob Gronkowski, Travis Kelce and George Kittle were all selected outside of the first round, well outside in the case of Kittle.

It’s an ugly curve for safeties. Don’t draft them in the first round. Instead teams can get them on the cheap in free agency.

On a recent episode of the excellent Wharton Moneyball podcast, Massey said that they found the likelihood that a player taken one positional ranking higher in the NFL would be better than the next was 52%, or roughly a coin flip. For quarterbacks, the likelihood rises to 60%.

Great article and complement to the free agency piece. Positional value seems to be incorporated into team building to a certain extent, but not enough based on all the information available. Teams spend so many resources to find small edges in scouting but they undervalue the market based comparative edges that exist.

Loved this. Will say I'm interested in how this relates to both the "there's no such thing as draft steals only draft reaches" wisdom of the crowds-concept and positional variability from draft to draft. Put in other words and in the context of this upcoming draft, if there's an early run how big of a consensus big board discount would be *too* big when it comes to taking a player in a premium position over (say) one of the TE?