Regime Time Horizons and the Principal-Agent Problem

Every franchise wants to win, but incentives promote maximizing short-term job security over longer-term championship odds

As part of my interview with FiveThirtyEight’s Josh Hermsmeyer on this week’s Unexpected Points podcast, we discussed the state of NFL front offices, and had generally pessimistic assessments.

While I’ve previously been more optimistic than Josh about the influx of young, superficially analytically inclined general managers entering the NFL, there are issues that persist in negatively affecting decision-making. I want to highlight an important one that is impossible to mitigate without an overhaul of the incentive structure for general managers and coaches: the principal-agent problem.

Investopedia defines the principal-agent problem:

The principal-agent problem is a conflict in priorities between the owner of an asset and the person to whom control of the asset has been delegated.

In the case of NFL franchises, the agent is the general manager, who is responsible - along with head coaches, to varying degrees - for building the strength of the team. In addition to the actual NFL owner, we can also think of the fan base as principal stakeholders in the team, with longer time horizons for their fandom.

The principal-agent problem is often discussed in business contexts, with C-suite executives working to ensure bonuses based on short-term results over a company’s equity holders’ desire to increase long-term profitability.

The conflict in NFL franchises isn’t monetary bonuses, but between the short-term incentive of job preservation against the long-term goal of building a championship-level roster, which often requires short-term costs. Very few general managers are fired and then installed again at the top of one of only 32 NFL franchises, so the one-and-done nature of the position adds to the already strong incentive to hold onto your current job at all costs.

THREE-AND-OUT FOR NFL COACHES AND FRONT OFFICES

Despite the theoretical patience of ownership when a new regime takes control - often formally expressed in 5- or 6-year contracts - you really have a maximum of three years to make a playoff run happen, sometimes fewer.

It’s more difficult to get general manager historical data, but for all head coaches who began their careers since 2000, only four made it beyond three seasons if they didn’t make the playoffs or have a winning record, and two of those four had multiple 8-8 seasons in their first three years. The two remaining coaches who survived to their fourth seasons with only losing records were Gus Bradley (Jaguars) and Mike Nolan (49ers), who were both fired in-season the following year.

In a new regime’s first draft, they can practically make decisions that won’t bear fruit for another season or two, like trading back or taking slower-developing positions. But even entering their second season, the ticking of the clock can cloud decision-making for coaches and front offices, and in year-3 teams are generally in complete win-now mode.

Job preservation quickly becomes the biggest conflict in the principal-agent problem between coaches and front offices against their teams’ ownership and fan bases. And nowhere does it become clearer than in decisions teams make to hold onto fine-but-not-elite quarterbacks, instead of making rational risk-reward bets on talented prospects.

QUARTERBACK AVERSION

In the NFL, the most powerful way to boost championship odds is finding an elite player at the game’s most important position, the quarterback. Yet, draft-after-draft we see teams pass at taking shots at the position, mostly recently letting a flawed-but-skilled passer like Will Levis slide to the second round.

Whatever you think about Levis as a prospect, the risk of taking him in the middle of the first round is likely overstated. Among the half dozen young quarterbacks that are on top of the NFL right now, Lamar Jackson mistakenly fell to the end of the first round, Jalen Hurts lasted all the way until the second round, and many questions surrounded the profiles of Josh Allen and Justin Herbert when they entered the NFL.

Even Patrick Mahomes wasn’t a slam-dunk top quarterback prospect, taken after Mitchell Trubisky and several non-quarterbacks in the 2017 draft. The success of somewhat flawed prospects in the NFL shows that the risk in passing on a talented quarterback can be just as great as taking one.

Many first round picks fail without much publicity, yet a quarterback picks in the first round, with surplus value equivalent to a couple third-round picks, can be viewed as make-or-break for the franchise.

Just look at the team that eventually ended up taking Levis, the Tennessee Titans. In the last few first rounds of the draft, the Titans have taken a question-mark receiver in Treylon Burks, and two near full misses in Isaiah Wilson (only played one NFL game) and Caleb Farley (missed most of his first two seasons with injuries). I’m sure that their selection of Levis near the top of the second round will receive much more scrutiny than those prior, higher-value picks, plus their 2023 first-round pick Peter Skronski, who could end up playing guard in the NFL.

There is a real short-term downside to an early quarterback pick beyond the media focus and hype: they usually aren’t good in their first season. Looking at all rookie and veteran quarterback seasons since 2000 (minimum 200 dropbacks), the distributions of total expected points added (EPA) for quarterback plays (dropbacks and designed runs) are vastly different.

The median outcome for a rookie is slightly negative expected points added, which understates the relative performance to overall NFL dropbacks that generally produce positive EPA. Several quarterbacks who went on to have successful career struggled mightily as rookies, including Alex Smith (-95.1 EPA), Jared Goff (-80.3), Matthew Stafford (-65 EPA), Derek Carr (-61.2), Trevor Lawrence (-32.4), Eli Manning (-29.8), Lamar Jackson (-8.4) and Josh Allen (-1.4).

It’s honestly shocking how often a quarterback selection outside of a coaches first season leads to their immediate dismissal, even if they aren’t the ultimate decision-maker on the pick, and we know that successful quarterbacks often struggle as rookies.

Some recent examples of coaches fired during or immediately after a quarterback’s rookie season: Jack Del Rio (Blaine Gabbert), Pat Shurmur (Brandon Weeden) Dennis Allen (Derek Carr), Jeff Fisher (Jared Goff), Todd Bowles (Sam Darnold), Jay Gruden (Dwayne Haskins), and Matt Nagy (Justin Fields).

Even if a new head coaching hire coincides with a rookie quarterback pick, it doesn’t assure job security if the quarterback’s performance is near historical lows, like we saw with Steve Wilks and Josh Rosen in Arizona. Maybe you could put Urban Meyer in that same category, but obviously there was a lot going on with Meyer’s leadership outside of Lawrence’s rookie-year struggles. Quarterback selections that are explicit risk-reward bets in the second round, like DeShone Kizer for the Browns, still can lead to the in-season firing in the front office (R.I.P. Sashi Brown) and the coach Hue Jackson only hanging on for one more partial season.

LIONS AND FALCONS HEAR THE CLOCK TICKING

A couple good examples of regimes that likely feel a great deal of pressure to win in their third seasons are the Lions and Falcons. Both teams had losing records the last two years, but come into 2023 with some positivity around their chances to succeed, especially in weaker divisions.

The Lions have the best odds to win the NFC North.

And the Falcons are second in the NFC South.

Both teams were in position to trade up and pick Anthony Richardson, or stay pat (maybe even trade back) and take Will Levis in the first round. But as I showed above, the floor outcomes for either rookie would be severely worse than Jared Goff, and probably even lower than third-round pick Desmond Ridder, who at least showed he had some potential in four starts as a rookie.

If either the Lions or Falcons took a quarterback in the first round, their chances to have a winning season and playoff birth - the two ways to extend the current regimes’ tenures - would almost certainly have gone down, even if it raised their Super Bowl chances in 2024 and beyond. Not only would they likely get mediocre quarterback play or worse in 2023, but they wouldn’t have the contributions of the non-quarterback rookies they did select in the draft.

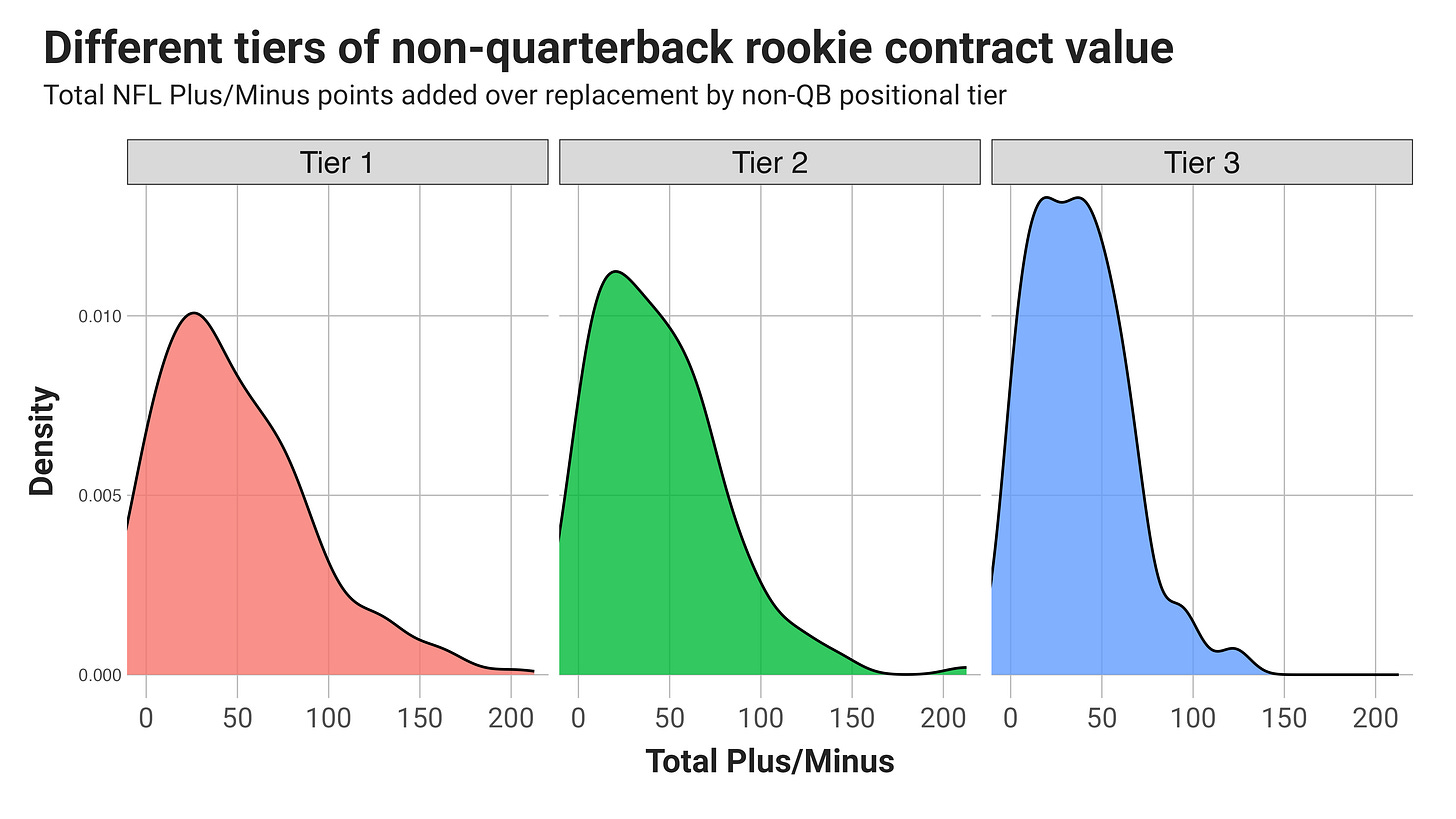

It might just be coincidental, but the Lions and Falcons also took what I’ve labeled as “Tier 3” non-quarterback positions in the first round.

While the full rookie-contract distributions for different non-quarterback show the downside of the third tier, they actually perform better as rookies. So you could argue that taking a running back and off-ball linebacker in the first round is an optimal player for the Lions’ coaches and front office, if short-term job preservation is the objective.

Any way you slice it, the regimes for the Lions and Falcons were in a tough spot entering their third seasons with reasonable chances to make the playoffs if the bottom doesn’t fall out at quarterback. Combining that with the history of coaches and general managers fired in similar situations after rookie quarterback selections, and it becomes obvious how the incentives went against them taking a quarterback.

FIXING THE PRINCIPAL-AGENT PROBLEM

The best way to fix a problem of misaligned incentives is to align them. We know that quarterback picks are basically coin-flips, even high in the draft. We also know that quarterbacks tend to struggle as rookies. Lastly, we know a non-elite quarterback selection doesn’t sink permanently sink Super Bowl chances, as we’ve seen the Bucs survive post-Winston, the Rams post-Goff and the Eagles post-Wentz.

Knowing all this, coaches and front offices need to be assured that they will only be judged on what they can reasonably control. If the objective measures for a team’s performance outside of the rookie quarterback’s play are improving or steady, that shouldn’t lead to a coach firing, despite the win-loss record suffering.

Adding an extra year or two of guarantees to coach and general manager contracts for drafting a top quarterback prospect could mitigate the irrational costs associated with doing so, and realign the long-term nature of ownership and fandom with job tenures for the front offices and coaches.

As usual, a focus on process over results, and having reasonable expectations and understandings of how quarterback performance ages will solve much of the misalignment of the win-now incentives of the NFL, but ownership and fans have to recognize rewards don’t come without risks.

Last sentence should say "rewards don’t come *without* risks." ?

Reminds me that GMs despite the lofty qualifications and salaries are people first. As your former collogues on the PFF main pod like to say, the GM's first job is not getting fired. Thanks for the read as always, Kevin.