Early Offseason MVP Betting Market Review

Patrick Mahomes' unique brilliance might be getting boring for some, but it isn't going anywhere

This is the first of a series of posts on the different early offseason betting markets for NFL futures. We’re going to start at the top with most valuable player, and then move down through other player-level awards, before moving on to team futures, totals and seasonal player props.

You can argue that the MVP betting market is one of the more efficient available in the offseason: it’s a competition at a single position and the stability of quarterback performance is higher than anywhere else on the field (perhaps excepting Justin Tucker field goals).

I agree that relative efficiency is generally the case in MVP betting markets, we could be in a multi-year window where the biases of bettors and bookmakers alike leave consistent value at the top. There’s also a commonly accepted narrative about the MVP award that likely is influencing both sides of the betting equation, despite the fact - as I will show - that the evidence flies in the face of it.

This post will have a few sections:

Historical review of MVP winners and which metrics are most correlated with winning.

My process for assessing quarterback quality and range of career outcomes, then adjusting for seasonal variance.

Comparison of my quarterback performance projections for the 2023 NFL to current MVP odds, highlighting values with long or short odds.

HISTORICAL MVP REVIEW

Like any good empiricist I like to look at the evidence first before applying modeling and logic to the process. Many start and finish with logic, which can feel ironclad, yet be based on commonly assumed realities rather than actual facts.

One of the more common fallacious assumptions about the MVP market is that because it’s a voter-based award - and voters are people, and people are biased and influenced by narrative - you can’t reply too heavily on analytical measures for player value. It’s right to assume that most of the 50 voters selected by the Associated Press to vote on their suite of awards doesn’t know what EPA stands for (expected points added), let alone have any idea how it’s calculated. The logic then goes that EPA can’t be a meaningful measure of voter sentiment if it don’t matter for their voting process.

I don’t disagree with anything in the above paragraph. EPA doesn’t matter, generally, to MVP voters. We can’t measure exactly the thinking that goes into the award. In order to project voter opinions on player value, we need to find which proxies, or alternate figures, best represent how voters will perceive players and form their opinions. Our feelings and logic may point to EPA as a poor proxy for voter sentiment due to its complicity and opacity, but the historical evidence tells a different story.

Looking at quarterback MVP winners since 2001 (earliest full-season data available using the nflverse data), we see that nearly all ended the regular season as the most efficient quarterback in the NFL (min 14 games played).

In this 22 year period, the 20 quarterback MVPs (three years running backs were MVP, one season two quarterbacks shared the award) included 15 who finished the regular season ranked first in EPA per play, four were second, and only one finished outside of the top-2 ranks (Cam Newton was fifth in 2015). One of the second place finishers doesn’t even weigh against the correlation or MVP and efficiency, as Steve McNair and Peyton Manning tied in the voting for the 2003 season, so both of them couldn’t finish ranked first (it was McNair and Manning was second).

Two of the other three MVPs who ranked second in efficiency had the highest total EPA generated that year, but on higher volume and slightly lower efficiency than one other quarterback. Total EPA, and volume dependence, is something to think about when projecting the award, though it’s correlation with MVP has been slightly weaker than EPA per play.

Newton is, again, the outlier at fifth in total EPA his MVP season, while Aaron Rodgers (fourth 2021), Peyton Manning (third 2008), Tom Brady (second 2010) and McNair (second 2003) all won the award without adding the most in total value. Rodgers had a lower-volume season in 2021, but was first in EPA per play. Manning got a lot of credit in 2008 for producing a 12-win team despite a weakening roster. Brady only trailed Philip Rivers by few than 2 EPA in 2010, despite dropping back 70 fewer times. And McNair split the MVP vote with Manning in 2003, on higher efficiency but only 14 games played.

EPA might not matter explicitly to voters, but I haven’t found a better proxy for voter sentiment. Only two of the 20 quarterback MVPs since 2001 didn’t finish ranked first in either EPA per play or total EPA: Newton (fifth and fifth) and Manning (second and third). EPA does an excellent job of capturing team value added on quarterback-involved plays, and voters’ sense of value appears to be closely attuned.

What EPA also doesn’t better than any other quarterback metric is correlate with winning, since it’s the most accurate assessment of actual, points-based value on the field. EPA has power as a direct proxy for voter sentiment on quarterbacks, and it’s likely a confounding factor in the relationship between voter sentiment and quarterback team wins. The most powerful determinant for team wins is quarterback efficiency.

Double-digit team wins appear to be a necessity for quarterback MVPs, yet it’s a tough needle to thread for a team to have an extraordinarily efficient offense and not win at least 11 games. Seasons like the Texans in 2020 happen (4-12 despite Deshaun Watson finishing sixth in EPA per play), but they can’t be reasonably predicted.

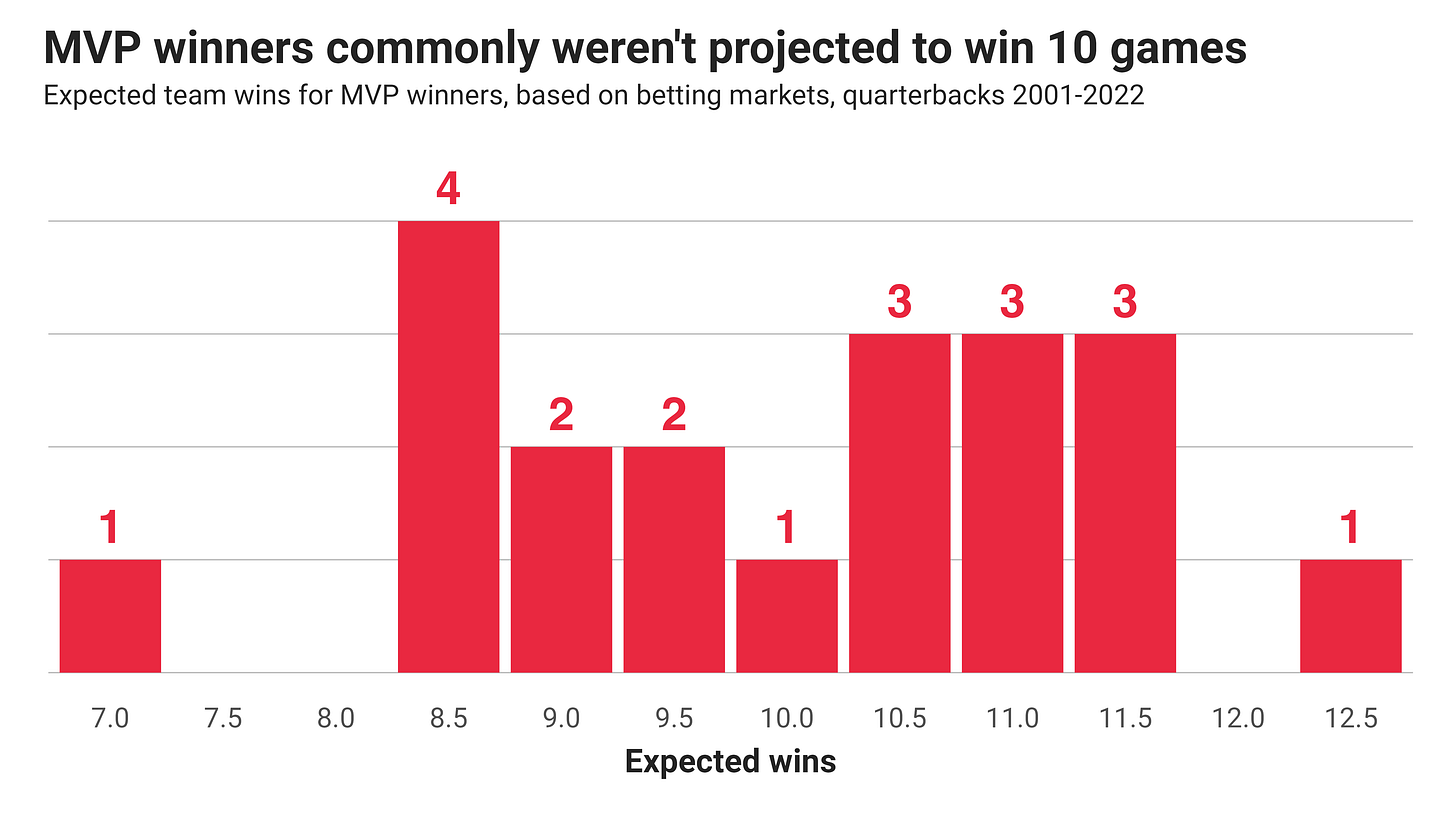

When we contrast actual wins to pre-season projected team wins for MVP winners (according to betting markets), we see that many of the quarterbacks who went on to win the award weren’t projected to be on double-digit win teams.

Matt Ryan’s MVP win in 2016 is an outlier, playing on an Atlanta Falcons teams only projected for seven wins in the pre-season. Then again, who knows if Ryan would have even won the award without the four-game suspension of Tom Brady. Including Ryan, nearly half (nine of 20) of the recent MVP winners played on teams projected to win fewer than 10 games. Or course when looking at future years we need to keep in mind that most of these were expectations for a 16-game season.

The teams of MVP winners typically win significantly more games than expected, as often is the case when quarterbacks have MVP-type efficiency during the season. I wouldn’t totally discount team strength outside of the positions that will affect quarterback performance (defense and non-quarterback rushing), but they’re likely overweighted in the minds of MVP bettors. If a team is projected for fewer than eight wins in a season, it’s normally because the reasonable assumption is that the quarterback is bad, not that they can’t win double-digit games with an MVP-level season in efficiency from their quarterback.

FORECASTING QUARTERBACK PERFORMANCE

Now that we’ve established that EPA per play measuring quarterback efficiency is a good proxy for MVP voters’ sentiment, we still have to figure out the best way to project efficiency. You can get 90% of the way there calculating career EPA per play rates for the likely quarterbacks, but even that rank ordering doesn’t equate to probability of being the most efficient quarterback, or at least in the top-2.

I like to use Bayesian updating for my quarterback projections, which incorporates past historical performance for individual quarterbacks, weighed for the size of the samples they’ve produced and our understanding of the variance of quarterback results.

Bayesian updating gives us not only a median, or “best guess”, figure how well we believe a quarterback will perform in the future, but also a range of outcomes that narrows as we learn more about them. With a decade of great performance from Aaron Rodgers we know that he’s likely a better quarterback than Kenny Pickett, but Pickett’s range of outcomes is much wider due to our lack of evidence and lower confidence in who he will be after only seeing him drop back to pass roughly 450 times as a rookie (Rodgers has more than 8,600 career dropbacks). A player can have simultaneously have a lower expected, or median outcome while having a higher probability of attaining a top, MVP-level outcome.

In the past, I’ve applied this methodology to look at how good we think a player will be going forward over their careers, not a specific season. The range of outcomes over a longer timeframe are smaller, and if we project the top young quarterbacks right now in that way, it doesn’t look like anyone has even a chance to be more efficient than Mahomes.